Scientists using data from Chinese lunar orbiters have discovered what they think is a mass of granite 30 miles wide deep under the surface of the moon.

Located under the moon’s far side, it’s unlike anything found before. Presented today at the at the Goldschmidt Conference in Lyon, France, a paper has also been published in the journal Nature.

On Earth, granite is the result of the cooling of molten lava from a volcano. It could be from a volcano that last erupted 3.5 billion years ago, but it’s still generating heat.

It’s a stunning find because until now granite on the moon was found only in traces within lunar rock brought back to the Earth on the Apollo missions of the 1960s and 1970s. It was thought to require Earth-like conditions such as plate tectonics.

Scientists Left Puzzled

The area, between two lunar craters called Compton and Belkovich, is believed to be an extinct volcanic caldera. “We have discovered extra heat coming out of the ground at a location on the moon believed to be a long dead volcano,” said Matthew Siegler, a research professor and research scientist with the Planetary Science Institute and Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas. “We were a bit puzzled when we found it.”

The mass of granite likely formed from unerupted lava cooling below the ancient volcano. It’s radioactive, probably because it contains uranium and thorium, which is why the area appears hot compared to the rest of the frigid lunar surface.

Bunch of Volcanoes

The granite clump was found using microwave-wavelength readings from antennae on China’s Chang’e-1 and Chang’e-2 lunar orbiters.

“Any big body of granite that we find on Earth used to feed a big bunch of volcanoes, much like a large system is feeding the Cascade volcanoes in the Pacific Northwest today,” said Siegler. “This is more Earth-like than we had imagined can be produced on the moon.”

The find is so important because it appears to come from Earth-like processes. “Geologically-speaking, it’s quite hard to make granite without water and plate tectonics, which is why we really don’t see that type of rock on other planets,” said Professor Stephen M. Elardo, NASA Early Career Fellow; Assistant Professor, Dept. of Geological Sciences, University of Florida, who was not involved in the research.

“So if this finding by Siegler and colleagues holds up, it’s going to be massively important for how we think about the internal workings of other rocky bodies in the solar system.”

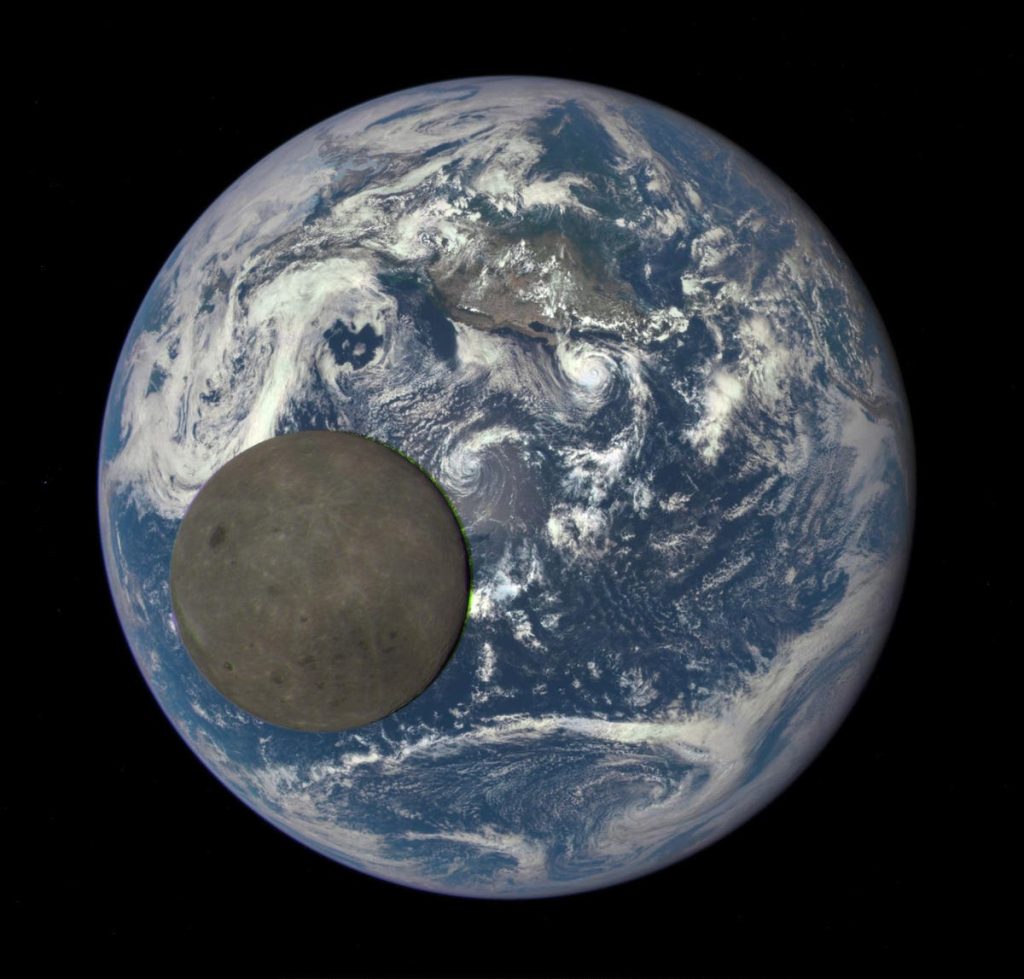

The moon’s far side is impossible to see from Earth because it’s also facing away. The moon is tidally locked to Earth, so it always shows the same familiar face.

Wishing you clear skies and wide eyes.

Read the full article here