Even among microorganisms, the fine line between life and death can appear to be razor thin. But in adapting to extreme conditions here on Earth, some forms of bacteria successfully retreat into dormant phases where they can persist as biological spores.

This is particularly useful in cold environments here on Earth. But astrobiologists are particularly intrigued by the possibility that bacterial spores may also persist in the frigid subsurface conditions of the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn.

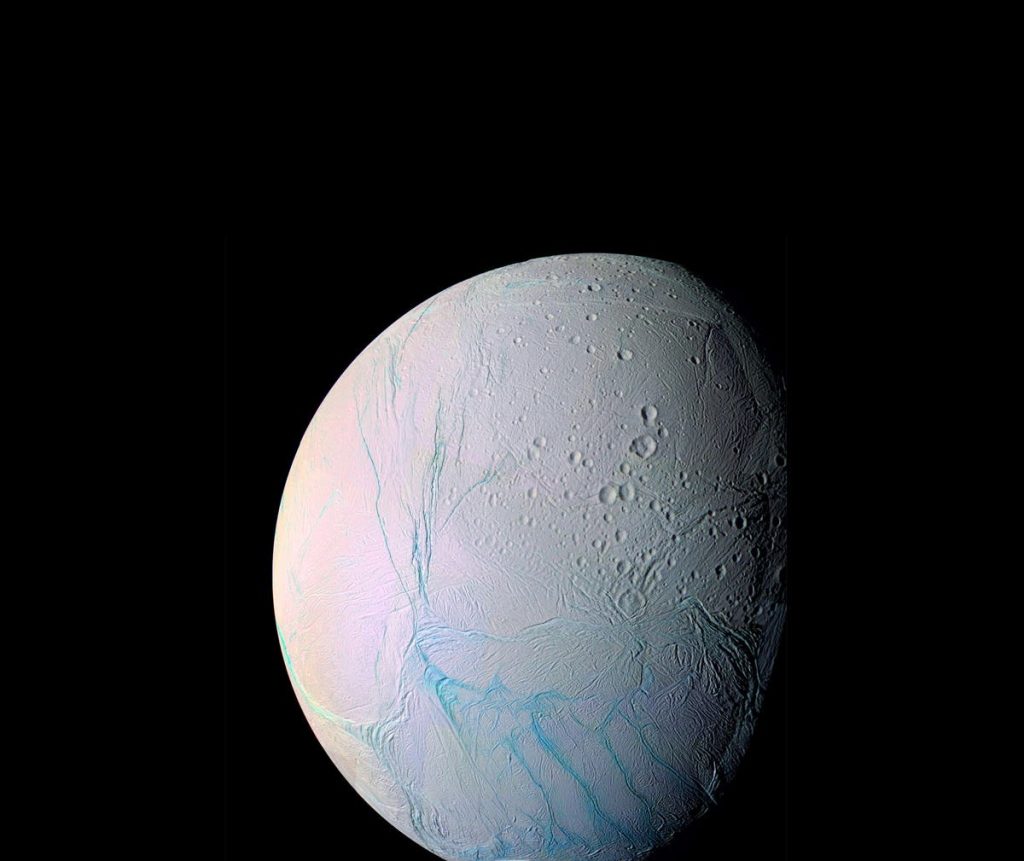

There, such bacteria may have first evolved on the warm seafloors of Jupiter’s moon of Europa or Saturn’s moon of Enceladus. From there, some form of cryovolcanism may have deposited the bacteria into the icy subsurfaces or surface, forming spores in the process.

Counterintuitively, the colder the conditions, the better these spores seem to like it. Or so indicates recent research by planetary scientist Edith Fayolle and colleagues at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab.

Do bacterial spores constitute life?

Bacterial spores are a life form, but they are dormant, Fayolle told me via email. Some bacteria respond to environmental stress by moving into this dormant spore phase, she says. This spore phase constitutes a regular bacterial cell forming a very hardy coat around its genetic material, she notes.

Spores are one of the most resilient life forms we know, says Fayolle. We find them everywhere on Earth; they do not replicate; they do not grow, but the genetic material of the spore-forming microorganism is preserved, she says. They can also wake-up when the conditions around them are more favorable and turn back into a regular cell, capable of replicating, Fayolle says.

Fayolle and colleagues picked a hardy Earth microorganism known as Bacillus Subtilis and studied its spores being irradiated by sun-like light in the laboratory.

Bacillus Subtilis is a bacteria present almost everywhere on Earth, including in our gut, says Fayolle. It can turn into a spore when environmental conditions are not favorable to its functioning, she says. That’s why we decided to study it; in order to better comprehend the limits for viability at the surface of icy moons, she notes.

I measure how many spores could be reactivated and be functional by counting how many bacterial colonies grew on the petri dish, says Fayolle.

We observed that the spores were more viable after we irradiated them at cryogenic temperatures rather than at room temperatures, she says. In other words, their capacity to wake up and turn back into a regular cell capable of replication was greater at very low temperatures, she says. That’s because low temperatures actually slow down the rate of damage induced by radiation, says Fayolle.

How long could such bacterial spores last on an icy moon’s surface?

My hunch is that, in the absence of radiation, microorganisms that are as resilient as bacterial spores would stay viable at cold temperatures for a very long time, says Fayolle. We know that on Earth, less hardy microorganisms can stay viable for years when preserved at cryogenic temperatures, she says.

Could there be bacterial spores on one of these icy moons that might stand a chance of being reactivated?

If microorganisms are present in the liquid beneath these icy moons, it might be possible for them to end up on the surface, says Fayolle. These moon surfaces are subjected to solar radiation and high-energy charged particles, she cautions. So, the likelihood of a viable microorganism at the very top surface of an icy world is low, says Fayolle.

Which icy moon may be best for such spores?

Saturn’s moon of Enceladus, says Fayolle.

If microorganisms could form in Enceladus’ sub-surface ocean and make their way to its surface, its south pole would give bacterial spores the best chance to survive, says Fayolle. The radiation levels are low, Enceladus’ south pole experiences long winters, and the redeposition of icy grains from the moon’s outgassing vapor plumes could shield the microorganisms from damage, she says.

Read the full article here