If extraterrestrial intelligent life is out there —- and everybody and their brother now seems to think so —- it could hypothetically be as much as a few billion years ahead of us.

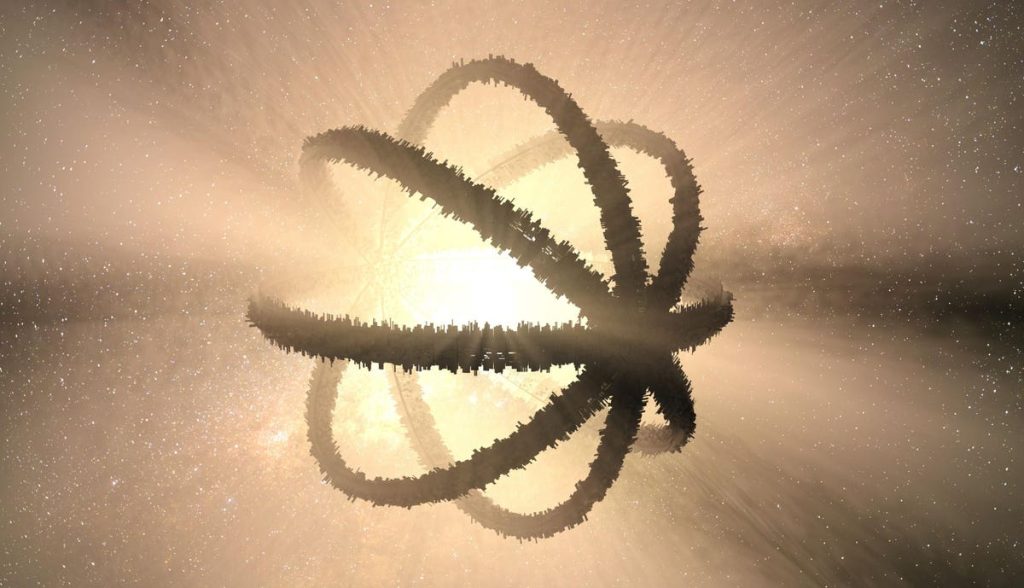

In the ongoing hunt for techno-signatures —- the sexy new moniker given to the hunt for large-scale alien astro-engineering projects, the concept of a Dyson sphere would entail partially or wholly harnessing a given star’s solar energy in ways that we can only imagine. First proposed by the late British-American physicist Freeman Dyson, such spheres would hypothetically be used to power gigantic supercomputers, artificial habitats, to propel spacecraft, or for advanced interstellar communication.

If one Swedish astronomer is correct, intelligent aliens might not even choose to harness energy from the star they’re living around. Given that some 75 percent of the stars in the Milky Way are M-type red dwarfs, E.T. may be harnessing the energy of one of these nearby tiny stars even as we speak.

To learn more during a recent visit to Stockholm, Erik Zackrisson, an astronomer at Sweden’s Uppsala University, sat down with me to discuss his latest thoughts on the subject.

Currently, Zackrisson and one of his doctoral students are studying the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Gaia stellar catalog as well as infrared stellar catalogs to look for Dyson sphere candidates.

Zackrisson and Uppsala University doctoral student, Matias Suazo, are submitting a journal paper to The Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS). They started with 5 million of the nearest stars and have now flagged around 10 faint, red dwarf stars as potential candidates for harboring Dyson spheres. None are well-known objects. But their next paper will detail follow-up observations of these candidate stars.

As For Why Aliens Might Choose To Harness A Red Dwarf?

The first reason is that they have estimated lifetimes that range from tens of billions to tens of trillions of years. Thus, they represent an energy source that can span pretty much span the age of the universe.

They might harness a red dwarf just because it was nearby, Zackrisson told me.

How Do You Look For Dyson Spheres?

They would appear dim in the optical and bright in the infrared; that’s the first giveaway, says Zackrisson. The problem is that there are natural astronomical objects that also behave that way, he says. The most common type is a young star because they are embedded in dust that glows in the infrared and blocks some fraction of the star’s optical light, he says.

Some people argue that the aliens would be so advanced that they wouldn’t waste anything, says Zackrisson. But as we understand the laws of thermodynamics, when you convert one form of energy to another, you always end up with a waste product, he says. A Dyson sphere would have to get rid of this waste energy somehow, says Zackrisson. And the most natural way for this to happen is through blackbody radiation (thermal emission of heat in the infrared), he says.

What’s the most difficult aspect of proving the detection of a Dyson sphere?

This is the problem with Dyson spheres; you’re looking for outliers in astronomical data, says Zackrisson. It’s very difficult to convince yourself that it’s a Dyson sphere, or just extreme astrophysics that we haven’t really seen before, he says.

A Dyson sphere would radiate as a pure continuum in the infrared; in other words, there would be no peaks in its spectrum.

If you have access to NASA’s Webb Space Telescope, you could get a spectrum in the infrared to see whether there are peaks or not, says Zackrisson. If there are peaks, you can just reject it as dust, he says.

Design A Search That’s Beneficial For Astronomy, No Matter The Result

If you’re not detecting Dyson spheres, or database glitches, then you’re at least detecting extreme astrophysics so astronomy will benefit, says Zackrisson. It is cheap and easy to do this research with existing databases, but it’s very time consuming, he says.

You want A.I. to basically do most of the pruning of your sample, so you yourself do not have to look at so many candidates, says Zackrisson. This can be a slow process, but we don’t have to do it all at once, he says.

Read the full article here