August 7, representatives of Cruise and Waymo appeared, opposite San Francisco officials, before the California Public Utilities Commission to deal with questions about controversial events involving robotaxis in the city. The first hour was about “unexpected stops,” a term which resulted in a fair bit of debate as both sides defined the term differently.

The CPUC had told attendees they would need to address questions about unexpected stops, particularly those involving first responders or disrupting traffic. Both Waymo and Cruise decided to provide statistics on what one called “Vehicle Rescue Events” (VRE) where a human rescue operator is dispatched to go to a stopped vehicle to solve the problem, sometimes by manually driving it out of the area or even back to the depot. City officials indicated their statistics were about all stops that caused a problem that was reported to them, and they claimed there were more such incidents.

Cruise offered the following statistics:

- They had 177 of these VREs from Juan 1 to July 18, 26 with a passenger on board.

- During that time they drove over 2.1M miles in SF, which they indicated was 10x more than all the other operators in the city (mostly Waymo.)

- This rate amounted to one VRE per 79,000 miles of passenger service, and 1 per 11,500 for all types of service, but that this has been steadily improving, and is now 1 per 30,000 miles. There have been no harm to passengers in any incident.

- Only 2 of these VREs involved emergency responders according to their notes. In contrast, they noted 168,000 encounters with emergency responders, solving over 98% of them fully autonomously.

- The average response time for a VRE rescue was 14 minutes. About 1/3rd involved a vehicle needing to be taken back to depot.

Waymo offered somewhat different calculations

- They have driven 3M miles (mostly outside in San Francisco) with 30,000 emergency vehicle encounters. (Waymo was more strict about limiting their reports to events with a passenger on board, because the CPUC authority is strictly over passenger services, not unmanned movement.)

- They report 58 “VRE” style events over the last 6 months. They also report that June was 80% less than earlier, implying a strong downward trend.

- Most (not quantified) of these events have been fixed and would not happen again in the same situation (presumably tested in sim.)

- Average retrieval time for a rescue was 10 minutes, sometimes as low as 2 minutes

- They only found 4 cases with 1st responders present, and in no cases where they impeded.

On the other hand, San Francisco officials, including top officials from the fire department, police and transit agency, wanted to report a different story:

- They report almost 600 incidents since launch (June 2022) and believe there are more

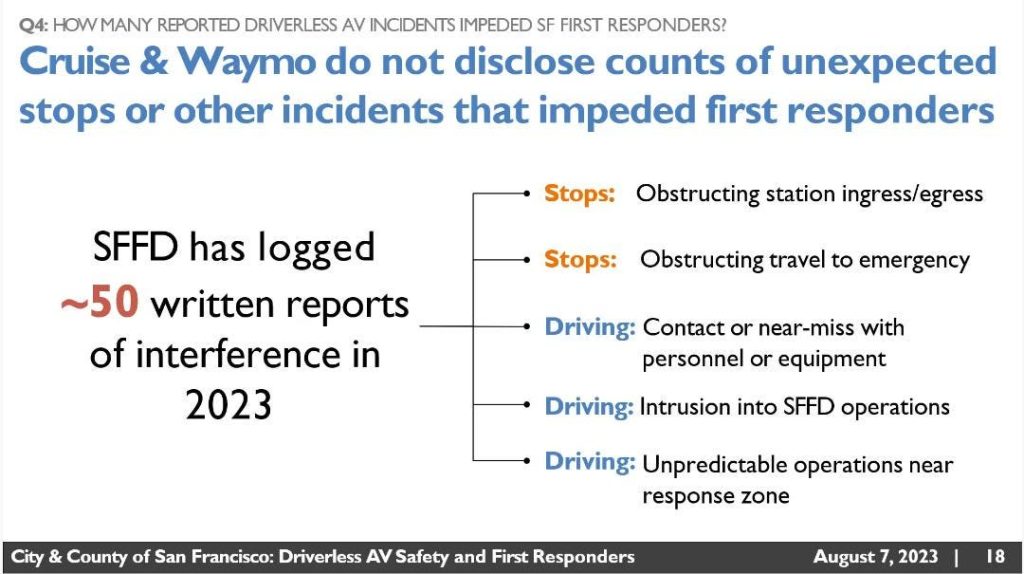

- SFFD has logged 50 reports in 2023 and logged 4 more the past weekend

- The most recent month (June) was the worst month — they do not agree that things are improving with time

- All SF officials lamented lack of 2-way communication with companies

Waymo and Cruise did take deliberate advantage of certain procedural items here. While it’s true that the CPUC only regulates passenger services, it’s also clear the public interest here goes beyond that, particular with emergency services. The commission should have understood that the questions needed stricter definitions to include events which seriously delayed traffic or emergency workers, not just events that needed a remote rescue. The companies indicated they were given only short notice to provide this data and did what they could. At the same time, the CPUC, which does indeed only regulate these vehicles as taxi services, is not the agency that should be considering these questions, and are only doing so under pressure from city officials who arguably overstepped by taking this route, as these matters are the province of the California DMV and NHTSA.

The resulting data is inconclusive. The most important question may be the difference of opinion on whether the rate of problems is improving or not. Waymo and Cruise both indicated they were improving, and that almost all past events were ones that were fixed and would not repeat. That is as it should be, and if it’s true, means that officials should have less cause for concern. Growing pains are expected and unavoidable — what matters is actual harm that takes place, and things which will follow a pattern and repeat. Humans as a group repeat their mistakes all the time and sometimes can’t be stopped, but robots are different, and properly managed, should not ever repeat the same mistake.

Training and interactions

The second section covered training, about which there was less controversy, though the officials again complained the training was mostly a one-way experience. They also objected to the fact that the companies work differently, forcing officers to take training for each company with double (or in the future quadruple) the time. They objected to the approach of asking officers to phone a company operations center (they don’t always carry phones) and the lack of input they had into the processes. Although the companies said that the ability for a vehicle to be manually driven by an emergency worker was done at the request of the emergency workers, they expressed that they did not have the time to do extra work to manage these vehicles and “babysit” them.

Both companies agreed it would be better to standardize procedures and to make interactions more intuitive, and report they are working on it. The companies should not have expected law enforcement agents to take space training in order to work with their vehicles, at least if you follow the principle that you must drive in the world you are given rather than forcing it to adapt to you — but hopefully this will change with time.

How to fix it?

The next session discussed what to do about problems. The position of the SF officials was that problems should never happen, and if they do, they must be resolved “immediately.” Their position is that a minute can be an immense amount of time in an emergency. Police feel similarly, that any command they issue should be acted on immediately, and that the vehicle code demands that.

LAFD agreed and want a system so that they can define “geofences” or “no-go zones” in a standard way so that all vehicles will avoid the emergency scenes.

Waymo agreed that situations should be resolved “as quickly as possible” though avoided promising that that is “immediately.”

Cruise indicated that they do immediately detect emergency scenes and connect a remote advisor every time, and those advisors can talk to people near the car, roll down windows, give the vehicle a new path, and allow manual driving by a first responder.

Both sides seem to feel the other side isn’t communicating well. Perhaps some mediation would make sense to improve that. Cities will have to realize that some of these things are simply not under their authority and that’s a deliberate choice in order to reduce regulatory overload — but at the same time companies may be wise to work a little more closely with their pilot deployment cities, but tell cities they move into later that they should not expect much regulatory power to avoid the problem of companies being forced to work with thousands of authorities.

Mark Gruberg, a taxi driver representative expressed the view that vehicles “aren’t anywhere near ready in general” and called for slowing down deployment. He felt the approval hearing in 3 days will be a rubber stamp and the CPUC should collect more data.

Peter Lreo-Monoz from Silicon Valley Leadership Group expressed their support for Waymo, as did Ariel Wolf of the Autonomous Vehicle Industry Association who also asked whether CPUC hearings are the correct place for this issue — in general the statements from both Tech industry representatives and the Taxi driver representative matched closely with their expected financial interests.

Sharon Giovinazzao, an advocate for the blind, outlined the bad safety record of human drivers — including the drivers of emergency vehicles who are involved in many serious accidents, she reported.

Her questions did suggest one thing that was missing from these hearings, which is data on how often human drivers block traffic or interfere with emergency scenes, and for what duration. That robotaxis make mistakes — and will make more mistakes in their early pilots — is to be expected, and the important question is whether they cause more trouble than human drivers, and how that will trend into the future.

Cory Hohs of HAAS Alert promoted the system his company has built to allow communication of emergency operations to drivers, and is standard in many cities and emergency vehicles, and comes per-installed on fire trucks and ambulances. He asked why these systems are not already being used to solve this problem.

The last session had most of its focus on the Mobility Data Specification (MDS), a standard created in Los Angeles for data gathering and commands for Scooters and taxis among others. Most parties were not fans of it — it has a variety of privacy issues and offers a lot of command and control the city, more than members of the public might expect.

Analysis

The CPUC is really the wrong body to deal with the question of whether robotaxis are working well with emergency vehicles, and how they should. That doesn’t mean there aren’t issues, but they don’t belong with the agency that many regulates how they will provide ride service and passenger safety. If other agencies like the DMV find they don’t operate safely with traffic and emergency vehicles, the CPU’s main role should be to use that finding in their decisions on where to licence ride service.

Better data should be made available — via the DMV. There should be consensus on what incidents are problematic, how often they are happening, how often they happen with human drivers, and what the trends of improvement are. If things are improving, the regulatory hand should probably be light until problems persist, though there should be regular dialogue among the parties to make sure that everybody is aware of what’s happening.

At least today, the city official may not get the standard of “immediately” they hope for, where a car responds to their voice commands and gestures as well as an alert human. On the other hand, this is probably attainable in the future. Teams simply don’t seem to have put in full effort early at reaching this level of responsiveness. They should perhaps work to demonstrate where they will be going in the future to build confidence in all parties.

The vendors should indeed seek to get better data on where emergency situations are underway, and avoid them before they even get there — even before the emergency vehicles get there. The vendors are aware of the MDS used in LA and Waymo is participating in its drafting but have concerns over the privacy implications of existing designs which record where people travel. Made better, they should also be better at resolving emergency situations quickly. This may involve the use of remote driving in areas that have sufficient bandwidth and latency for this to work well.

With both Cruise and Waymo insisting that their remote operators are always connected in emergency situations, and that they can talk to people near the car, it is unclear what has caused the incidents where emergency workers seem to try to talk to a car which does not respond. More information on this should be disclosed.

Vendors should all work to present an extremely intuitive interface to emergency responders. It should be necessary for such people to take “training” in order to handle the basics of working with these vehicles. That doesn’t mean there aren’t things that should go into their regular training problems, particularly things which can’t readily be made intuitive. The interfaces should be fairly uniform, but being intuitive and easy to understand is even more important — after all, human drivers don’t have a standard interface, but we all know how to talk to them.

Read the full article here