Contrary to common belief, we are rarely rewarded for being ourselves. In fact, civilization is largely the result of our ability to self-censor and inhibit our spontaneous drives and natural impulses.

1) You should bring your “whole self” to work: There is no single job, career, or industry in which following this mantra will be beneficial, either to you or your employer. Unlike Freud, our colleagues, clients, and bosses have little interest in discovering who we really are “deep down”, particularly if it means having first hand experience of our character flaws, obnoxious tendencies, and bizarre beliefs. As it turns out, work is not an invitation to unleash the full spectrum of our identity on others, but a formal, rule-bound, and professional environment to which only certain aspects of our self are invited, and even fewer rewarded. Generally speaking, you will improve your performance, reputation, and success by displaying the best version of you, seeming (rather than being) genuine, and focusing more on pleasing others than yourself, all of which require a great deal of self-control, impression management, and being quite effective at inhibiting and repressing your self-centered impulses and unfiltered thoughts and emotions. The “real you”, in the sense of the uninhibited and spontaneous version of yourself that your closest friends and family are familiar with, is someone who at most four or five people in the world have learned to love, or at least tolerate, and not always for the entire weekend.

2) You should be true to your values: Well, it really depends on what these are. For instance, what if you are sexist, racist, xenophobic, or ageist? And how do we know or establish with some objectivity what the full index of problematic or undesirable values would be that could be added to this list; or what list of definitive good or positive values is? Furthermore, how do we know whether our values are correct or good, let alone the right ones? To be sure, history is replete with traumatic case studies of leaders, such as Hitler, Mao, and Lenin, who would have surely caused a lot less damage if they had been less true to their values. And in any society, business, or organization, there’s no shortage of individuals whose parasitic, toxic, and destructive effects on their groups would be significantly attenuated if only they managed to censor their crooked and immoral values for the sake of the everyone else. Needless to say, imposing our values on others would require us to assume that they are superior to theirs, and adopt a moral high ground, just like hiring for “culture fit” undermines cognitive diversity and imposes the values of the in-group or ruling elite on others. Clearly, a system or culture that allows for different values to co-exist in certain harmony seems preferable to a cult, but regardless of the group or system you belong to, there will be benefits to questioning your own values and entertaining the possibility that they may be wrong, as opposed to focusing on being true to them – in fact, this is also a good recipe for avoiding being part of a cult.

3) Authentic people are more successful: Not quite, though success does increase people’s tendency to act without consideration for what others think of them. In that sense, authenticity is a sign of privilege and entitlement. The more status you enjoy, the closer you are to the in-group or elite, the more you can afford to “just be yourself”, to the chagrin of everyone else. Indeed, the phrase “power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely” illustrates the fact that as people move up in any organizational hierarchy, which generally requires them to censor their unfiltered or authentic self, they are given license (or at least they perceive they are), to “just be themselves”, and behave free of any concerns for how others view them. To name just a few real world examples, Bill Cosby, Harvey Weinstein, Jeffrey Epstein, and Donald Trump felt no constraints or inhibitions when it came to behaving according to their own crooked, corrupt, and antisocial instincts, and their power, status, and wealth stopped witnesses from speaking up, exposing them, or pushing back. The only reason we are perpetually wishing that our leaders were humble, kind, and caring is that there’s a general tendency for people to be elected and selected for positions of power because of their selfish, aggressive, and narcissistic tendencies, and when they acquire power they experience little in the form of inhibitions or social pressures to repress or suppress their negative impact on others, assuming that their authentic and unfiltered self is actually charismatic, charming, or likable.

4) The best leaders are authentic: Certainly not. In fact, as Jeffrey Pfeffer notes in his excellent book Leadership BS, “to be authentic means to be in touch with and express one’s true feelings, and although that may sound good, it doesn’t make sense. Leaders don’t need to be true to themselves; in fact, being authentic is the opposite of what they should do.” Pfeffer’s argument aligns with consistent scientific evidence on the importance of political skills, emotional intelligence, and the personality of effective leaders. These studies, which account for nearly 50% of the variability in leadership emergence and effectiveness, indicate that leaders benefit enormously from inhibiting and controlling their authentic self and impulsive drives, such that high levels of self-control, conscientiousness, emotional stability and social desirability are the keys to helping them emerge and manage effectively. Add to this the importance of being data-driven, questioning your own intuition, and displaying rational compassion even when you don’t feel empathy for others, and you will hopefully appreciate that leadership talent is largely developed by constraining and containing the spontaneous and natural version of ourselves. By the same token, since people have a natural tendency to become more exaggerated versions of themselves, leadership development must help leaders go against their nature, so they can learn new habits, unlearn old ones, and mitigate the natural character flaws or problematic behaviors that would handicap them and their followers – which is why “playing to our strengths” is terrible advice for anyone wanting to improve, leader or otherwise.

5) Authenticity is good for diversity and inclusion: Although encouraging diverse, low status, and out-group individuals to “just be themselves” or “bring their whole self to work” may sound like a nice idea, there are strong counter-arguments to it. First, not everybody is interested in sharing aspects of their private or personal life with their work colleagues, so we shouldn’t assume such policies are appreciated by others (whoever they are). Second, there are few career-related and job performance benefits of displaying non-professional aspects of your self in work contexts, and the notion that others should accept or like us for “who we really are”, which would include our less functional and adaptive traits and habits, is at odds with reality: people want to see the best version of ourselves, especially in work settings. In line, what’s appreciated is our effort to be kind, tolerant, and a willingness to play by the established rules, even if we don’t fully agree with them. Third, unless organizations have created an inclusive climate, with true psychological safety, an open mindset, and a general environment where kindness, curiosity, and compassion are the norm, it is meaningless, if not irresponsible, to encourage those very individuals who are the likely target of prejudice, harassment, and antisocial behaviors to assume that they are truly invited to open up, share personal or intimate information, and bring private aspects of their identity to the workplace. This is not dissimilar to when organizations encourage women to “lean in” or “be confident”, while there are no real rewards, and there’s often a backlash, when they do. Diversity without inclusion doesn’t work, and you don’t create inclusion by throwing the ball to employees and asking them to fix things by changing their behavior; which is akin to asking them to fix themselves. Inclusion is created top-down rather than bottom-up, and unless leaders can create an environment in which people truly feel that they can express personal and private aspects of their selves – because they want to rather than are told – it makes little sense to celebrate authenticity as the solution to our diversity and inclusion problems.

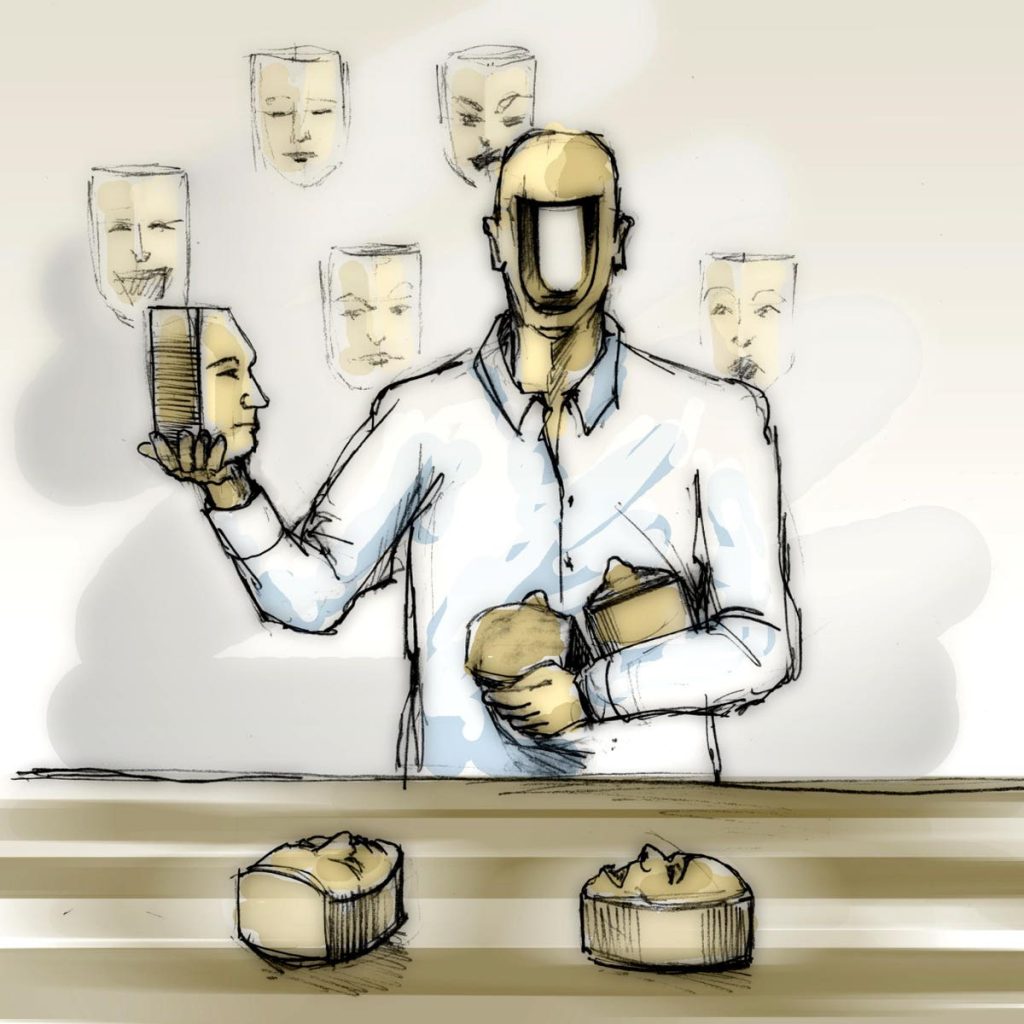

6) It is easy to know when someone is authentic: Not quite. As a matter of fact, philosophers and psychologists have been debating how to define authenticity for centuries, and there’s little consensus on this today. The reason is simple: no single definition or take on authenticity is without logical or empirical flaws. For example, some people define authenticity as “agency”, which implies that one can act without being influenced by anyone or anything, including society at large. This is nonsense: we come to this world as helpless humans and only survive because of our ability to learn everything we need from others, including how to act, think, and feel. And when we reach adult life, we are able to function as well-adjusted humans only because of our ability to internalize and follow rules, including when we ditch certain rules in favor of others. Besides, if someone tells us to act without consideration of what other people tell us, we are still following someone else’s precept, and being influenced by others. Likewise, when authenticity is defined as behavioral congruence between different situations (also known as behavioral consistency), we are not accounting for the critical importance to flex our behavior depending on the specific demands of a particular situation. So, behavioral rigidity does not make people authentic, and particularly not effective. Equally, the notion that we ought to express our “true self” in every situation is nonsensical since we all inhabit multiple selves, and self-complexity is part of our identity. What’s adaptive is to express or display the pertinent aspects of our identity in each relevant situation, keeping the other bits in the background. An even bigger problem is that there’s no way to know for sure whether someone, including yourself, is being authentic: people who seem authentic often put on a well choreographed persona, and are at best great “method actors” (their characters are believable because they believe they are in character). There’s also no way to tell whether we are being authentic ourselves: self-deception is ripe, so that we lie to ourselves all the time. And the conviction that we are fully aware of our true selves, or that a single dimension of our identity fully represents and encompasses the essence of who we are, is more common in psychosis than normal mental wellbeing. In normal humans, the rational position is to not really know who we really are, but nonetheless engage in humble and self-critical introspection, as well as internalization of other people’s feedback, to try to work it out – even if we can never find an answer. It should also be noted that the notion that some of our behaviors may be more “true” or “real” or “authentic” than others is logically incoherent: whatever we do, we can only be ourselves, even when we are trying to not be ourselves, and everything we do is indicative or representative of who we are, whether we like it or not, and whether it resonates with our self-views or not.

7) Authentic people are more emotionally intelligent: On the contrary, meta-analytic studies indicate that emotional intelligence is conceptually and empirically identical to impression management. In other words, people who are usually regarded as emotionally intelligent (by others rather than themselves), tend to behave in polite, pleasant, calm, and agreeable ways, because they are able to control their dark side tendencies to portray themselves in a positive manner when interacting with others. Accordingly, they score highly on measures of impression management and social desirability, which have been found to predict higher levels of job performance and career success. We may not know who you really are deep down, and whether you are acting in a genuine or sincere way or not, but your ability to come across as rewarding to deal with, composed, and kind, will generally boost your status and accomplishments in life. It may sound bad when we call it “impression management”, and good when we call it “emotional intelligence”, but they are basically the same thing.

8) Most people know who they really are: They don’t, which obviously creates a big challenge for those seeking to act “authentically”. One of the most widely replicated findings in behavioral science is that self-deception is far more common than self-awareness. In other words, we fool ourselves all the time, as illustrated in our general tendency to believe that we are smarter and better than others, and that we actually are; that our failures are not our fault, while our successes are the product of our talents and merit; and that people are right when they praise us but wrong when they criticize us. When most people think about themselves, including their self and who they are, they are able to construct a pleasant, logical, and optimistic narrative about their identity, which doesn’t mean that they can get others to believe it or buy into it. What matters in every area of life is not how well or highly you think of yourself, but whether you can get others to agree with you. Social skills is translating your self-views into other people’s views of you, or getting others to agree with the picture of yourself that you’d like to see. Contrary to common belief, the best way to understand who we really are is to internalize other people’s views of us. As the great David Bowie noted “I am only the person the greatest number of people think I am”.

Read the full article here