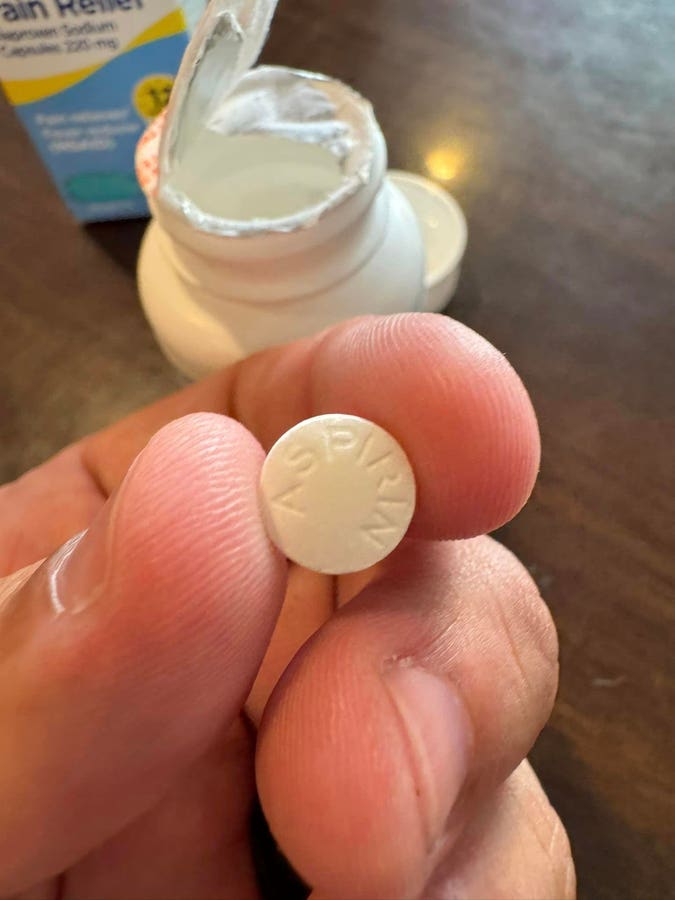

A friend, epidemiologist Dr. René Najera, posted on social media last weekend that he went to a Walmart in Mt. Airy, Maryland to buy some naproxen and acetaminophen. When he went to open the package, “The bottle inside it was upside down, which seemed odd. Then I opened the bottle and peeled off the seal. And I noticed the pills were small, round, and white. The caplets on the packaging are bigger, blue, and oval.” His wife was going to look up the numeric code on the pill, but they found “aspirin” imprinted on the other side.

Najera said he “filled out the FDA report while sitting there at the restaurant.” They then returned to the Walmart. He spoke with the pharmacist, who took another box of naproxen from the shelf. It was a different lot, and she opened it to see it was actual naproxen blue oval caplets. It was. The pharmacist said she’d contact the store manager to pull other bottles of the same size.

This type of a mislabeling problem appears to be uncommon. Still, I was told on background that quality product reports are not public information and that one can only pursue a Freedom of Information request. An FDA spokesman also said that for this type of case, the company (here Walmart) would generally be the one to decide whether to issue a public alert or recall. An email to Walmart’s Global Communications, Global Social Responsibility and Media Relations representative yielded no information as of yet other than they are asking their supplier to investigate.

Sometimes, labeling errors occur in hospital pharmacies when personnel are preparing batches of drugs. In one such case, syringes were being prepared for anesthesia, including a neuromuscular blocking agent, propofol, and 1% lidocaine. The labels were inadvertently switched, resulting in some patients being paralyzed and needing emergency respiratory support. Batching procedures were reviewed to ensure that such an error was not repeated.

This specific error with the aspirin substituted for naproxen was less likely to be life-threatening unless someone has a severe allergic reaction to aspirin. If someone took naproxen instead of aspirin, they could be at risk of a stroke or heart attack, as aspirin, which inhibits platelets, is an anticoagulant.

Background

Public protections began with the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, which emphasized truthful product labeling. There were no protections before that—people could sell any type of food or drug, regardless of quality. After, drugs had to meet “standards of strength, quality, and purity in the United States Pharmacopoeia and the National Formulary.” The law was expanded in 1938 with the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which allowed FDA oversight. This was prompted by the “elixir sulfanilamide” event, in which an untested antibiotic containing the toxin diethylene glycol poisoned and killed more than 100 people. The new act required the manufacturer to prove the drug was safe before selling it. The act required accurate reporting and labeling. Companies also had to monitor for adverse events. Later, clinical trials were required prior to a drug’s approval, looking at safety and efficacy.

Medication Errors

Other kinds of medication errors are much more common than factory mislabeling. Some common errors come from drugs having very similar names, such as Clonidine (a blood pressure med) vs. Clonazepam (a benzodiazepine used for seizures) or Metformin (to lower blood sugar) vs. Metronidazole (an antibiotic). These account for 29% of pharmacy dispensing errors.

Occasionally, bigger problems were reported. In 2008, heparin was contaminated with chondroitin sulfate, leading to several deaths and more than a hundred serious adverse events. And in 2012, counterfeit Avastin was found to contain no active anti-cancer drug.

Drug Recalls

The FDA notes that not all drug recalls are announced on its site or in the news. It does so if it feels there is a serious health threat.

A physician or consumer should report a problem through the FDA’s MedWatch safety reporting system here for prescription and over-the-counter meds, medical devices, prefilled syringes, formulas, cosmetics and food. Vaccine adverse events are reported through the VAERS system.

A search of MedWatch alerts in 2023 showed five recalls (of 590 total) due to labeling errors. One was of Betaxolol Tablets (an anti-hypertensive) because a single Oxycodone HCl tablet 5 mg was found on the packaging line after the product was packaged. KVK-Tech notified its distributors and customers.

One lot of Marlex Pharmaceuticals’ Digoxin 0.125 mg and one of its Digoxin 0.25 mg pills were recalled in August 2023 because the labels were reversed, resulting in serious dosage errors.

In 2022, there were six recalls (of 590 listed) due to mislabeling. The most similar was a mix-up between Clopidogrel (Plavix) 75mg tablets (an anticoagulant) and Atenolol 25mg (an anti-hypertensive). Others were different doses of the same medication.

While the mislabeling of Walmart’s naproxen is less likely to cause a serious adverse event or death than the above examples, it would be comforting to know that companies will issue alerts when they become aware of problems. In the meantime, all a consumer can do is to check labels and compare the pill in the bottle with the picture on the packaging.

Read the full article here