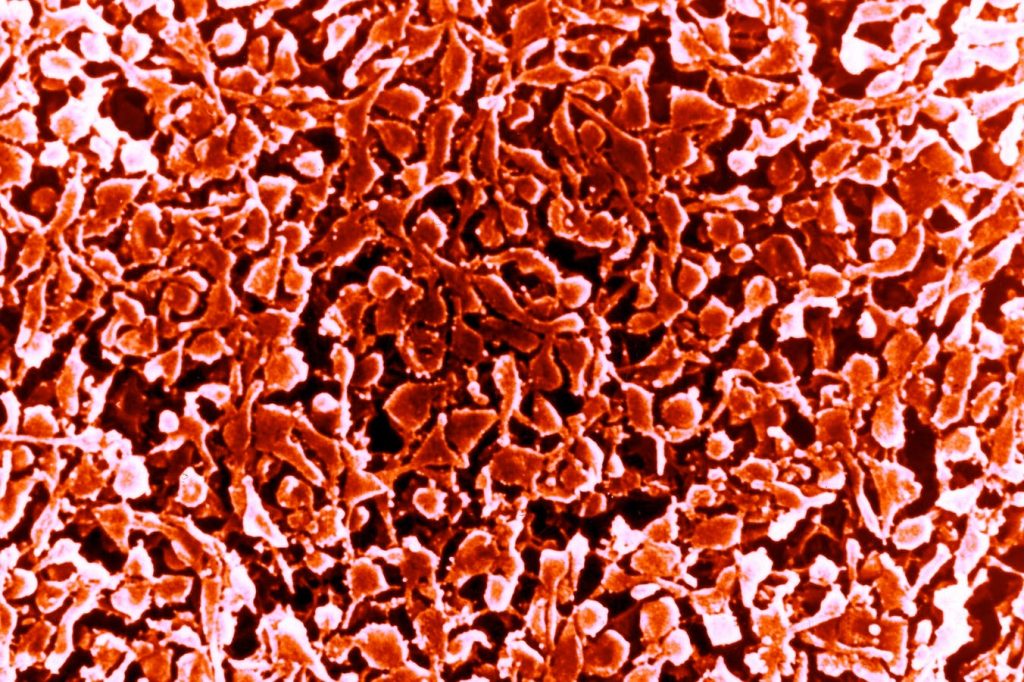

Mycoplasma pneumonia is in the news after the emergence of a series of outbreaks and hospitalizations were reported earlier this week in China, mainly impacting children. Drivers include respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, Covid-19 and perhaps most importantly, mycoplasma.

Chinese media reported several days ago that some the country’s pediatric medical centers were crowded with children who had fallen ill. The wave of pneumonia cases sweeping through parts of the country prompted the World Health Organization to request details on possible sources. Thus far, Chinese officials say causal agents include known pathogens, such as mycoplasma, RSV, influenza and SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes Covid-19).

Sometimes the bacterial illness caused by mycoplasma is called “walking pneumonia” because symptoms are often relatively mild but can last for weeks. Typically, mycoplasma pneumonia doesn’t require hospitalization. However, young children with a nascent immune system may be at greater risk of developing more serious disease.

Naturally, reports from China of clusters of undiagnosed cases of pneumonia and “overwhelmed” hospitals evoke memories of the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. In an interview yesterday, Maria Van Kerkhove, acting director of the WHO’s department of epidemic and pandemic preparedness and prevention, stated that “this is not the same situation that we were in in December 2019 and January 2020.”

Among other countries, China, South Korea and France are having serious epidemics, and the suspected main culprit is mycoplasma pneumonia.

In South Korea, confirmed cases of mycoplasma pneumonia more than doubled from mid October to mid November. According to a summary released by the Korean Agency for Disease Control and Prevention, 226 (96%) of the 236 hospitalized patients with acute bacterial respiratory infections during the second week of November had mycoplasma pneumonia. Notably, 80% of new patients are children under the age of five. The agency further suggested that the early onset of cold weather in Korea contributed to a “rapidly increasing” number of cases.

Cases of mycoplasma can occur at any time of the year, but tend to be more prevalent in winter. In the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, during each respective winter there is almost invariably an uptick in common infections such as influenza, colds (caused by a large number of different viruses) and respiratory syncytial virus which also produces cold-like symptoms.

Bacterial infections follow a similar seasonality. They’re usually opportunistic, in that they take advantage of an immune system that has been weakened by a virus. So, for instance, influenza, RSV and the common cold can sometimes lead to bronchitis or pneumonia, infections of the upper and lower respiratory tract, respectively.

Some have cited Covid-19 as what’s giving rise to the surge in mycoplasma, in that the still widely circulating virus lowers people’s immune defenses. While there is evidence of immune dysfunction persisting for many months or longer in some who contract Covid-19, it’s unclear whether there is evidence of widespread immune impairment due to SARS-CoV-2 throughout the population.

Alternatively, others claim the rise in mycoplasma infections has been brought about by what is sometimes termed “immunity debt” as there was a reduction of seasonal illnesses during Covid-19 lockdowns. Responding to the current situation in China, the WHO team specifically pointed to an “immunity gap created by the pandemic.” Social distancing, less travel and other measures designed to prevent the spread of Covid-19 could have lowered immunological defenses against diseases like influenza and RSV which in turn may have set the stage for opportunistic infections such as mycoplasma.

But there’s no consensus on the hypothesis advanced by the WHO team. In fact, experts have long expressed skepticism about whether there is a generalized immunity debt. For one thing, how long post-infection immunity lasts varies from one virus to another. And for flu viruses, for example, infection in one season may or may not offer protection in the next, depending on how closely related the two strains are.

Moreover, the cyclical nature of waves of mycoplasma infection—there was an upsurge in 2011, 2015 and 2019—suggest the current spike has little to do with a purported immunity gap.

Measures such as masking, ventilation, washing hands, avoiding close contact with others and staying home when sick are recommended to prevent the spread of mycoplasma, but also the viruses that can lead to mycoplasma. If ill, the pathogen can be treated with a wide variety of antibiotics, including azithromycin, but also tetracycline, macrolides and fluoroquinolones.

Read the full article here