Surging across the solar system from the sun, the solar wind carries charged particles that strike the planets, on Earth causing aurora, radio blackouts and, just occasionally, wreaking havoc with satellites and the electrical grid.

It waxes and wanes and, so far, has defied attempts to predict it—attempts that are getting ever more important as our technological society looks increasingly vulnerable to a once-in-a-century “black swan event” like a solar superstorm.

Such an event could destroy technology including satellites, internet cables, long-distance power lines and transformers.

NASA and solar physicists are on the case—and they just made a breakthrough.

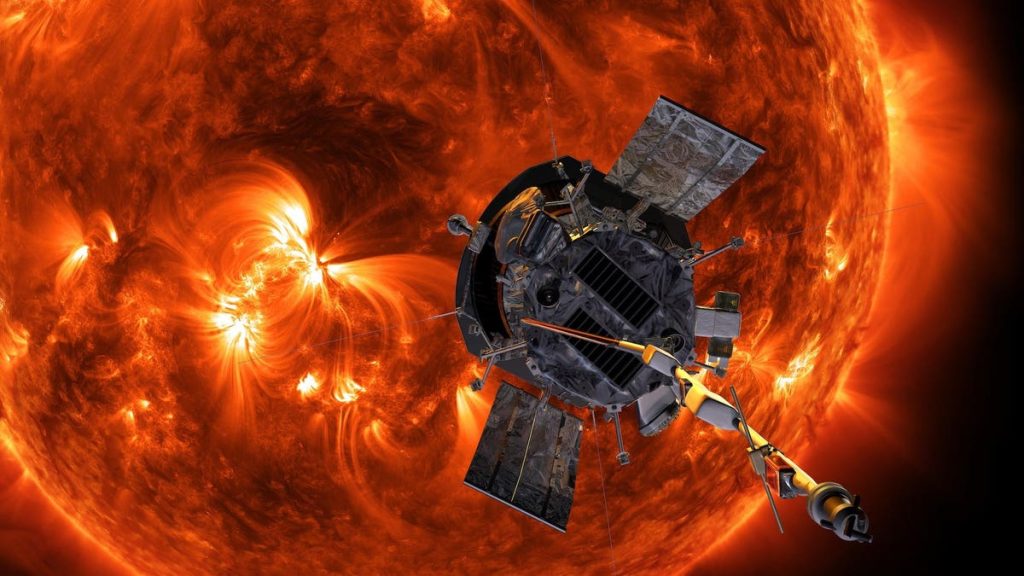

Working on the theory that predicting space weather means finding out where the solar wind comes from and how it’s created, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe was launched on August 12, 2018 to find the origin of the high-energy particles that comprise the solar wind.

A new paper published in Nature describes a close flyby of the sun during which it got to within 13 million miles. It was able to detect the fine structure of the solar wind close to where it is generated at the sun’s surface.

Predicting the solar wind

“Understanding the mechanism behind the sun’s wind is important for practical reasons on Earth,” said James Drake of the University of Maryland-College Park. “That’s going to affect our ability to understand how the sun releases energy and drives geomagnetic storms, which are a threat to our communication networks.”

During the flyby, Parker detected streams of high-energy particles that match what’s going on in what solar physicists call coronal holes—cooler, less dense regions in the sun’s outer atmosphere where open magnetic field lines expand outward. It suggests that the solar wind originates there.

The researchers liken the coronal holes to showerheads, with evenly spaced jets emerging from bright spots where magnetic field lines funnel into and out of the surface of the sun.

Solar maximum

Some thought Parker was launched too early in the solar cycle to get meaningful information. The sun has a sunspot cycle of roughly 11 years during which it waxes from solar minimum (the last one was in 2019) to solar maximum, the latter of which is characterized by lots of sunspots and more common solar flares—and is coming up in 2024/2025.

Coronal holes develop only at the sun’s poles during solar minimum, but in the years around solar maximum—right now—the sun’s magnetic field flips and they appear all over the surface. That has consequences for Earth, which gets blasted by more intense solar wind, and thus more frequent geomagnetic storms.

“There was some consternation at the beginning of the solar probe mission that we’re going to launch this thing right into the quietest, most dull part of the solar cycle,” said Stuart D. Bale, a professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley. “But I think without that, we would never have understood this. It would have been just too messy. I think we’re lucky that we launched it in the solar minimum.”

Parker’s journey

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe completed its 15th close approach to the sun (out of a total of 24) on March 17, 2023, coming within 5.3 million miles while traveling at 364,619 miles per hour. Its next close flyby of the sun will occur on June 22, 2023 when it once again gets to within 5.3 million miles.

As the sun is now entering solar maximum its activity is becoming more chaotic and it may be more difficult to make such precise observations of specific processes, but in late 2024 and 2025 Parker will make its three closest flybys at just 4.2 million miles from the sun—the limit before its instruments would melt.

Wishing you clear skies and wide eyes.

Read the full article here