The share of firms raising worker compensation reached record-high levels in the past few years, reaching 51% in June 2022. The most difficult cost to cut is compensation. It is also the largest cost for most small employer firms. When the costs of non-compensation inputs fall, the benefit drops to the bottom line and can be passed on to customers by reducing selling prices. Competition is the force that gets this to happen. But when those cost inputs fall because of a slowing economy, wages generally stay the same; they are commitments made to individuals. The only way wage costs fall is if employees are dismissed or suspend more flexible components of compensation including bonuses, 401k matches, etc. Workers who are let go may find a job elsewhere, but quite likely at a lower level of compensation. And a replacement can be hired at a lower wage. This reduces labor costs for firms collectively, while raising the level of unemployment for those who can’t get re-employed. This process takes time, contributing to the “stickiness” of labor costs even as prices fall. Owners will reluctantly let go of workers for whom they struggled to hire and retain while workers were in short supply.

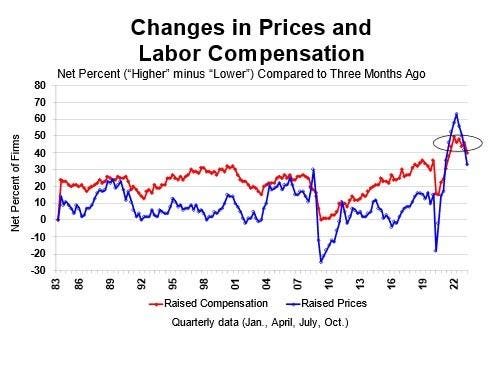

Chart 1 shows that labor costs and selling prices are highly correlated. However, movements in the net percent of owners raising compensation are less volatile than the percent raising selling prices which are easier to change than wages. In the last few years, the percent raising prices has declined much faster from its peak than has the net percent raising compensation – “sticky.” This makes it more difficult for the Fed to reduce the overall inflation rate because labor costs are the major operating cost for most small firms. This problem will vary in severity across industries.

Table 1 shows the percent of firms raising compensation and selling prices in broad industry categories. The percent raising compensation in the first quarter was highest in finance and real estate (48%) followed by construction (47%), professional services (46%) and surprisingly, retail (45%). These firms were also among the firms raising prices at very high rates, with the exception of professional services where 46% raised compensation but only 18% raised selling prices. Construction and retail led the price hike parade (59% raised), followed by 54% of wholesale firms and 52% in finance (higher mortgage rates).

Consumer spending has continued to be solid, fending off reasons to cut prices and, in industries like construction and retail, providing the opportunity to raise them. The Federal Reserve’s strategy is simple, get people to spend less and competition for a shrinking consumer spend will induce firms to lower prices. Presto, inflation falls. Heavy government spending has kept incomes rising and kept spending solid, showing little inclination to slow. The rapid rise in the Federal Funds rate did precipitate some banking problems as depositors suddenly had other investments available that paid higher interest than savings accounts. But the inflation rate is close to 5%, way above the 2% target for inflation policy. Although the FOMC unanimously voted to raise rates in their last meeting, a pause in rate hikes has become more likely as the Fed will want to give their aggressive policy some more time to work before taking rates even higher (as Volcker had to in the 1980s). A continued downward trend in Chart 1 will indicate that the strategy is working.

Read the full article here