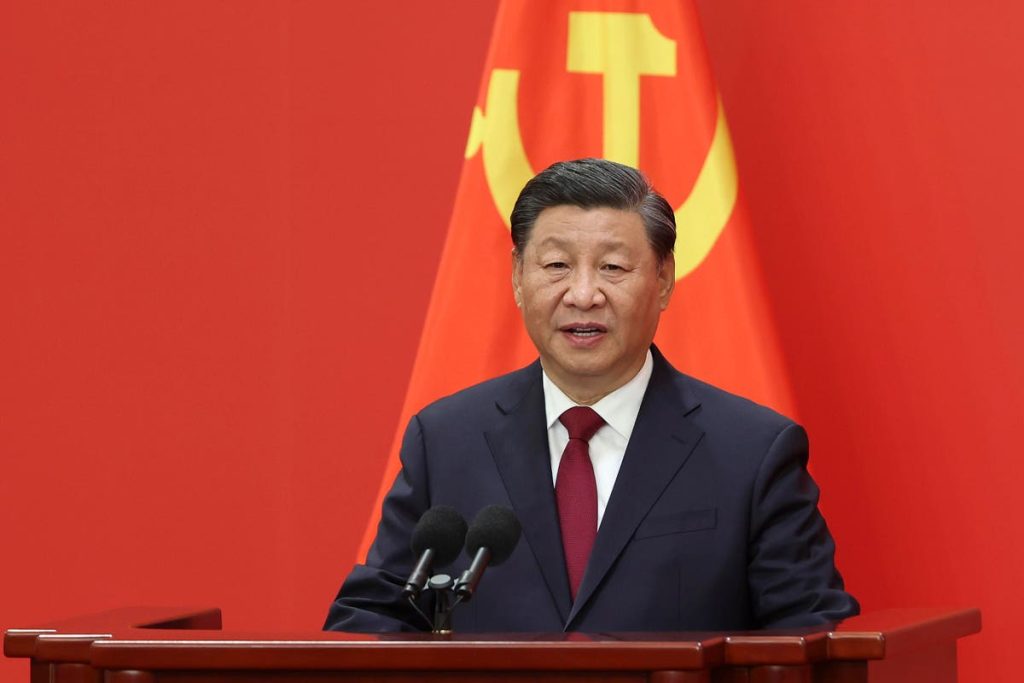

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s ambitious economic objectives are facing headwinds. Since taking office in 2013, Xi has wrought a major change in Chinese economic policy. All his predecessors, from Deng Xaioping in the late 1970s to Hu Jintao earlier in this century, had the straightforward aim of promoting growth to develop China’s economy at every level. They wanted to secure China’s stature globally and keep domestic peace by improving the living standards of the Chinese people. Xi wants something more particular and frankly more militant. He aims to minimize China’s dependence on other nations and maximize its ability to coerce those other nations. His plans are not working smoothly at all. It is not apparent that they ever could have.

Xi justifies his ambition on the expectation that the “powerful gravitational field” of China’s state-controlled market will reshape supply chains in Beijing’s favor. To exercise such overwhelming control, Xi has tried to corner the global market in a number of critical areas. China already produces the bulk of the world’s electric vehicles (EVs) and lithium batteries. It also plays a big role producing inputs to many of the world’s pharmaceuticals. The same could be said of windmills and solar panels. China also controls flows of the rare earth elements so necessary to the production of many of these products.

To these, Xi wants to add global dominance in low-end computer chips, creating an oversupply that will drive foreign competition out of business. His plans also seek Chinese dominance in high-end technologies, some through organic development but mostly by using trade to force transfers from the west and Japan and by outright theft. The effort at such particularized control has made him and his government less and less tolerant of private Chinese business largely because of its insistence on following profits instead of Beijing’s directions.

But these plans have run into difficulties. For one, Washington and Tokyo, as well as Europe to a lesser extent seem to have awakened to Beijing’s strategy and begun to push back. The United States now has legislation to thwart Beijing’s plan to add semiconductors to the list of essential products over which China has control. America now subsidizes semiconductor production in the United States and further forbids the sale of advanced chips and chip-making equipment to China. Japan and the Netherlands have joined Washington in these bans. Meanwhile Tokyo has made efforts to get the G-7 countries to acquire assets around the world to block China getting a stranglehold on rare earth elements. Even Europe talks about de-coupling from China, though it remains reluctant to use the word.

At the same time, western and Japanese producers have shown an ever-greater reluctance to invest in China. Apple, for example, has decided to move the assembly of its iPads from China to Vietnam. Samsung is making similar decisions on its production in China. Some 95 percent of multinationals have expressed concerned about the risk of doing business in China, up from 62 percent that said the same only two years ago. To a large extent, a sharp rise in Chinese wages is driving away this foreign investment but it is also going because of concerns about how the reliability of Chinese production and impatience with Beijing’s increasingly aggressive practices on trade as well as its strident demands for technology transfers.

Xi, remarkably, has lost domestic support. His criticisms of private business’ lack of patriotism and unwillingness to support party policies has clearly undermined confidence among private business managers. Unsure of their firms’ futures in China, they have held back investments in productive facilities. These have only grown a paltry 0.6 percent in the past year. Xi, concerned about this lack of economic support has of late softened his rhetoric, referring to entrepreneurs as “our own people,” but so far to little effect.

China may yet make headway on Xi’s plans. Its domestic market is, after all, so large that the west and Japan can hardly ignore it. But otherwise it seems as though Beijing has overplayed its hand. Had Xi and his cronies in the Forbidden City gone a little slower with their demands – in trade, diplomacy, and even military spheres – it might have taken longer for the west and Japan’s well as private foreign business wake up to Beijing’s open hostility. Even if China’s leadership had been more subtle, it is not apparent the program is logically sound. It seems to carry a fundamental inconsistency. A nation cannot be independent of the world, as Xi wants, and dominate its trade at the same time. To dominate trade, it must engage in it, and that makes if vulnerable to both buyers and sellers. That fact alone might defeat Xi, however determined he is or blundering his foreign opposition.

Read the full article here