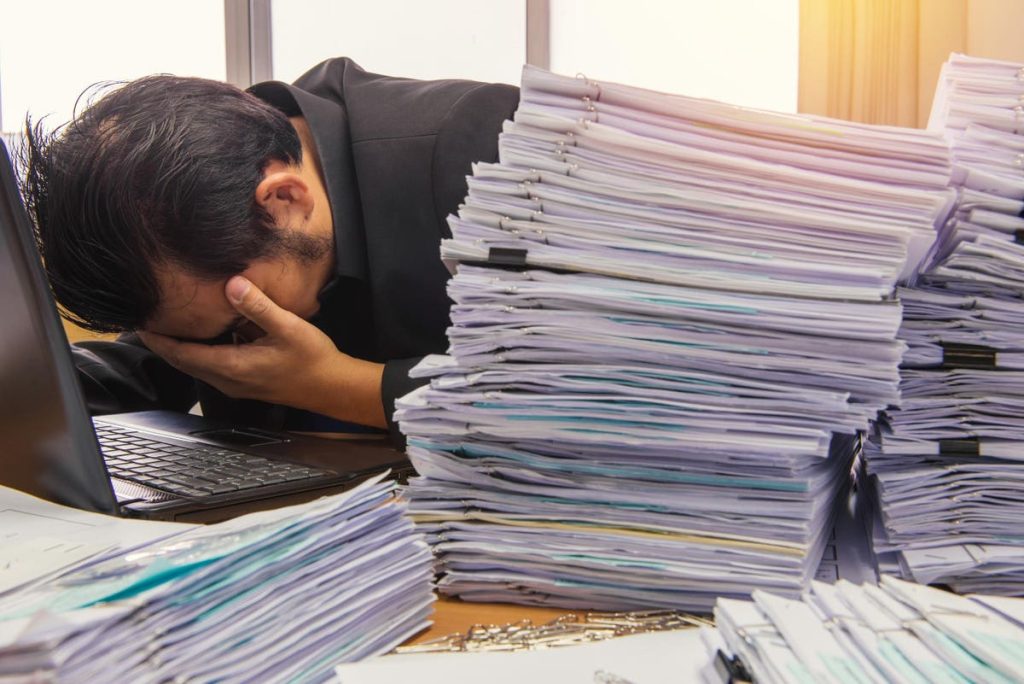

Recent governance policy refinements from several leading asset management firms are likely to create more work for the board’s nominating and governance committee.

These new refinements recognize the governance risks arising from over-committed directors, and call on corporate boards to more aggressively confront issues of director overboarding. For most companies, the pressure to address director commitment concerns will be manifested in the development and maintenance of a formal overboarding policy and disclosure of how the board will monitor oversight of the rollout of such policy.

The focus on overboarding first meaningfully arose during the Sarbanes-Oxley era, when breakdowns in corporate governance practices were a contributing factor to the notorious scandals (thus prompting both the eponymous statute, and related corporate responsibility practices). Particular criticism was attributed to outside directors who failed to contribute sufficient time and attentiveness to their oversight obligations, in part due to the demands of other board service and similar commitments.

Post-Sarbanes governance principles thus encouraged boards to address expectations regarding director time commitments and the extent to which other factors (e.g., other board memberships, employment distractions, health considerations) threatened the quality of individual director service to the board. But no hard and fast limits arose from that environment.

In recent years, several major asset management and institutional investment firms adopted firm positions on the issue of director overboarding in their proxy voting guidelines for U.S. portfolio companies. Similarly, several leading proxy advisor companies adopted guidelines opposing the election of CEOs and directors who exceeded specific thresholds on board commitment.

What’s new is the decision of several of these leading companies to move away from strict application of their own overboarding guidelines, in favor of greater reliance on nominating and governance committees to enforce director commitment practices. The sense is that well-governed corporate boards, not asset managers, are best suited to make subjective decisions regarding the caliber and time commitment of individual directors.

For example, State Street Global Advisors is discontinuing its use of numerical limits to identify instances of overboarding. Instead, it will vote against the chair of the nominating/governance committee of S&P 500 companies that fail to disclose an internal policy on director time commitments.

Similarly, Vanguard now calls on companies to adopt a formal overboarding policy and to disclose the board’s oversight of the implementation of that policy. In that regard, Vanguard seeks disclosure of the process for establishing that policy and the frequency of its review to ensure its ongoing relevance.

These policy refinements reflect greater governance sensitivity to the appropriate management of directors’ increasing time commitments. State Street CEO, Yie-Hsin Hung, observed that “…directors are busier than ever, reporting a 25% increase both in formal board meetings and number of days spent on director work — often serving on multiple boards simultaneously”. Such a substantial increase in directors’ workloads risks degrading overall board effectiveness over time.

This move away from the numerical limit reflects an awareness that seat limits don’t always reflect a complete view of director effectiveness. For example, director time commitment can also be impacted by directors’ service on private-equity or boards of large nonprofit organizations, both of which can require intensive time. Commitment can also be impacted by participation in leadership roles such as board or committee officer positions.

These refinements are consistent with the emphasis on director engagement reflected in governance principles promoted by the National Association of Corporate Directors (“NACD”). In its recently released guidelines, A Framework for Governing Into the Future, NACD recognizes that “…more is required of directors to stay well informed and to be available on a far more frequent and flexible basis.” Such requirements, in turn “… may require directors to rethink other commitments.”

An enhanced focus on director commitment may also reduce the risk of “tokenism” within the director community, arising from the nomination of already over-committed diverse directors without considering broader candidate pools from diverse communities.

The refined overboarding policies of the leading asset management firms reflect the importance of a robust engagement culture within corporate governance structures. Emerging risks such as ESG issues, and increasing oversight obligations arising from the Delaware courts combine with traditional strategic and financial issues to increase the demands on directors time and attention.

The ultimate message is that boards, across industry sectors, must be more focused on managing the increasing time commitments of their directors.

Directors, in turn, must be prepared to embrace the time and energy required by board service, including that which may arise from unanticipated situations. Avoiding overboarding risks is thus a shared board/director responsibility.

Read the full article here