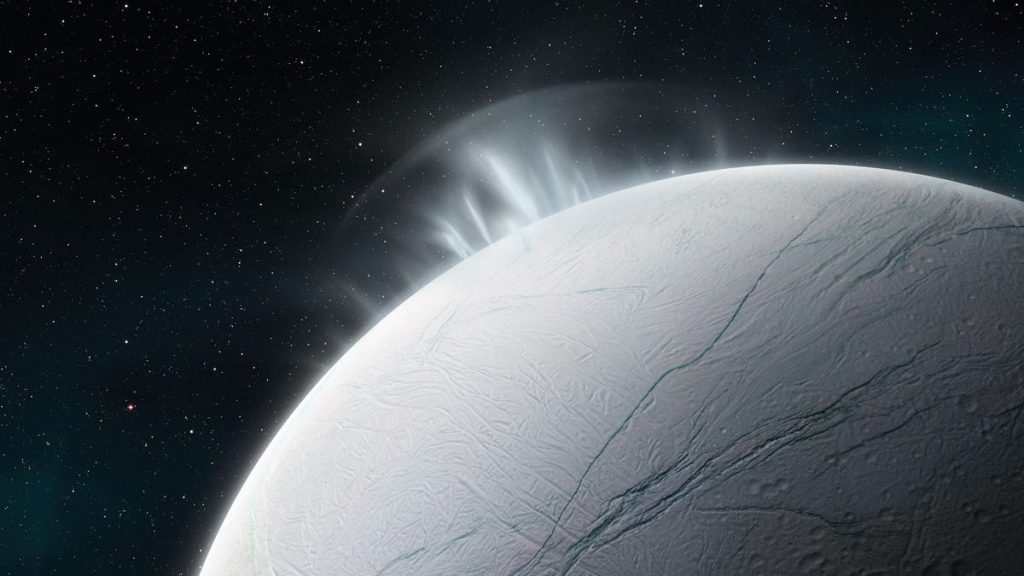

The tiny moon of Enceladus is quickly becoming ground zero for astrobiologists hunting for signs of life elsewhere in the solar system.

A paper published today in Nature reveals the detection of phosphates on Saturn’s sixth-largest satellite—an element thought to be an essential element for habitability largely because it’s necessary to create DNA and RNA.

It comes in the wake of the discovery in May by the James Webb Space Telescope of a 6,000 miles long jet of ice particles, water vapour and organic chemicals spilling into space through the icy crust of Enceladus.

Huge step forward

Never before detected in oceans beyond those on Earth, the discovery of phosphorus—previously thought to be scarce at Enceladus—is a big step forward in our understanding of the solar system’s ocean worlds. They also include Titan at Saturn, Jupiter’s moons Europa, Callisto and Ganymede, some moons of Uranus and Ceres in the asteroid belt.

The new science comes from data collected by NASA’s spacecraft Cassini, which was at Saturn between 2004 and 2017. During that time it saw jets hundreds of miles long spewing from Enceladus and its Cosmic Dust Analyzer was able to collect data on the ice grains within the jet.

The new analysis of that data has revealed the presence of phosphates. It’s of critical importance for life-hunters because not only do biological processes require phosphates, but despite being an icy world Enceladus has an environment that could support life—a subterranean ocean.

That ocean is precisely where the ice particles came from.

Subterranean ocean

Just 310 miles/500 kilometers in diameter, Enceladus—which is geologically active because of the gravitational pull of Saturn and its other moons—is a top target for astrobiologists searching for life off Earth because under icy crust is a 25 miles/40 kilometers deep liquid water ocean complete with rocky seafloor.

It’s thought micro-organisms and “extremophiles” could exist around hydrothermal vents there—exactly where the researchers think that phosphates could be in abundance.

The detection of phosphates in the jets—in the form of orthophosphate ions—was in such concentrations that the researchers have calculated that phosphorus might be 100 times more concentrated in Enceladus’ ocean higher than in Earth’s oceans.

Cue ‘OrbiLander’

A NASA mission may get the chance to land on Enceladus and confirm the detection of phosphates—and much more besides. Tentatively planned for launch in October 2038 (with a backup in November 2039) to arrive in 2050, the Enceladus Orbilander mission would orbit the moon twice per day for 200 days specifically to sample the contents of those jets up-close and with more advanced instruments.

Crucially, OrbiLander would then dispatch a small lander to descend to the surface f Enceladus and stay for two years sampling the fall-back from the jets—the very stuff that makes the tiny moon so bright.

Wishing you clear skies and wide eyes.

Read the full article here