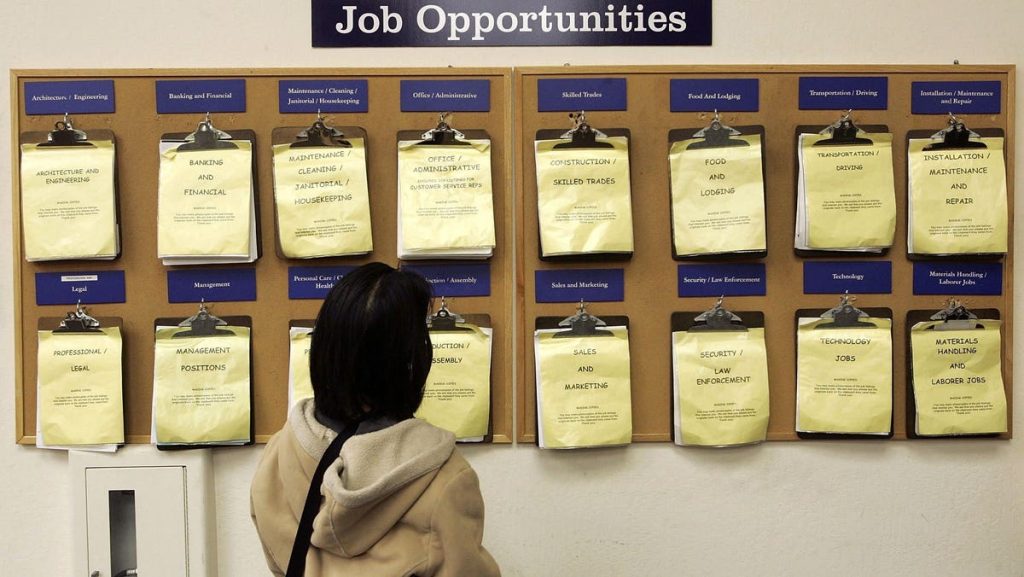

For many people, work has been a source of dissatisfaction. In the era of the Industrial Revolution, the risk was physical, with perilous conditions leading to injuries and even the loss of limbs. While the modern workplace might not pose the same physical threats, it still incites distress, albeit in subtler ways.

Author Melissa Swift encapsulates this by referring to work as dangerous, stating, “It’s dull, it’s frustrating, it’s confusing, it’s annoying, it’s intense, it’s biased, it’s misunderstood, and it’s performative.”

In her book Work Here Now: Think Like a Human and Build a Powerhouse Workplace, Swift investigates methods organizations can employ to dismiss antiquated, inhuman management practices and cultivate more human-centric workplaces. She interprets the current issue of burnout as an outcome of an intersection between industrial work practices and the intensification of work.

Before the Industrial Revolution, workers largely determined their own rhythm of work. Laborers knew that a field needed to be plowed, but they weren’t constrained by a specific deadline. It was acknowledged that accelerating the work rate might yield quicker results but would also detrimentally affect future productivity.

However, the advent of the Industrial Revolution redefined our perspective on work. Employers began quantifying machine performance and viewing human output through the same lens. Swift states, “The management tactics of the Industrial Revolution were all about getting people to think about time differently, which is eerily invasive.”

As Swift describes it, work intensification involves “trying to cram too many units of work into one unit of time.” This could range from picking an unreasonable amount of strawberries in an hour to managing an overload of 10 Zoom calls in a day.

This intensification doesn’t merely cause stress and exhaustion during work hours; it also infringes on our personal time—mornings, evenings, weekends, and even vacations. This concept, often dubbed “greedy work,” lures workers into working longer hours through overtime pay and the promise of advancement.

Swift interestingly correlates the surge of greedy work with the influx of women into the workplace. This established a barrier limiting the progress of women, who, generally speaking, shoulder a more significant proportion of society’s caregiving responsibilities. According to Swift, foreign-born workers and other groups are similarly hindered by greedy work. She articulates, “It’s a very interesting thing to think about from an inclusion perspective because it pushes already less included groups out of the workplace.”

So, what’s the solution? What can HR professionals and leaders do to create a more human-centric workplace? Swift presents four critical strategies for organizations to make substantial progress.

Firstly, organizations need to abolish the habit of treating employees as expendable. This necessitates recognizing and catering to basic human needs—such as sleep—across all tiers of the corporate structure. Swift affirms, “It’s really about treating people like people.”

Swift’s second recommendation is to encourage more realistic, perhaps even pessimistic, planning. With the inevitability of system failures and technology glitches, it’s the human workforce that steps in to rectify the issues. As Swift aptly points out, “Who steps in and fixes it? It’s the humans. When we are frantically improvising solutions, that’s exhausting.”

She asserts that humans are inherently resourceful, but constant firefighting without a plan B can lead to burnout. Thus, risk assessment and strategic planning are integral components of a human-centric management approach.

The third proposition is to dissociate people practices from financial metrics. It’s a misconception that accomplishing more in less time linearly contributes to growth. Consequently, we need to avoid setting unrealistic growth targets by burdening employees with excessive tasks.

“The interesting thing,” says Swift, “is that our flawed working practices are probably hampering the impact of technology because we’ve simply loaded too much onto humans.”

She suggests that organizations should employ metrics representing the efficient frontier of work rather than strictly assessing human productivity by financial or technological measures. She promotes the idea of eustress—a positive, motivating stress. There are no benefits of overstretching this limit; too much time in this zone can lead to burnout.

The fourth and final strategy is to reconsider the customer-centric model. According to Swift, “In the dot-com era, we made this fundamental overemphasis on customer centricity in a way that compromised the employee experience, and ironically, it doesn’t lead to the best customer experience either.”

In her book, Swift calls this the “boss baby” customer because companies have essentially made customers the bosses of their employees, but they can’t do a thing for themselves. This leads to employees becoming stressed, miserable, and overburdened from attempting to meet impractical customer expectations.

The future of work paints a promising, utopian picture. But it’s a vision that will remain a mirage unless leaders start dismantling harmful workplace practices. In conclusion, Swift leaves us with a compelling sentiment, “We need to pay more attention to the now than we do the future.”

Watch the full interview with Melissa Swift and Dan Pontefract on the Leadership NOW program below, or listen to it on your favorite podcast.

_______

Pre-order my next book, publishing in November, Work-Life Bloom: How to Nurture a Team That Flourishes, (You won’t want to miss digging in.)

Read the full article here