Back in the day, around the early 2000s, MTV made a slice-of-life commercial with Busta Rhymes depicting the East Coast rapper getting his driver’s license picture taken at the local DMV. An elderly worker notes Busta’s Brooklyn unchanging screwface and slightly annoyed posture, then peers through the camera lens. Much to the employee’s surprise, the camera captures Busta’s party-filled soul and his mischievous grin, punctuated with confetti raining down as he dances to a pulsating drum pattern. Unable to believe what he sees, the worker looks directly at Busta in real time, who still maintains his hardcore stance; however, when he looks through the camera again, party Busta reemerges. The photographer gives into the confusion and snaps the picture and the commercial ends with Busta’s completed driver’s license showing his true gregarious spirit.

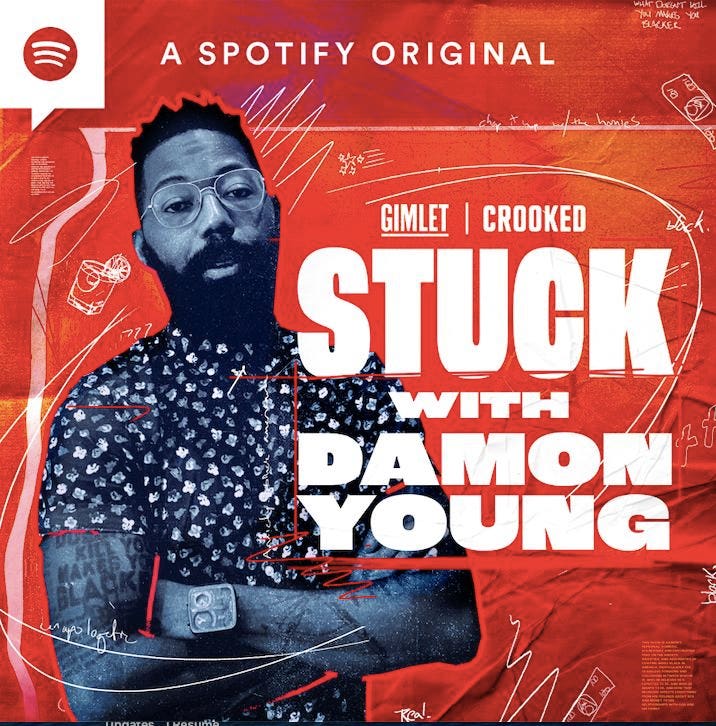

The comical scenario perfectly embodies “writer, critic, humorist, satirist, and professional Black person,” Damon Young, as he describes himself. A quick Google search will pull up images capturing Young’s deadpan expression that masks the sardonic, energetic wit of a societal savant who offers versatility “from anthropological satire and absurdist racial insights to razor-sharp cultural critique and unflinching indictments of privilege and bias,” which often is reflected in his articles, his book What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker: A Memoir In Essays and now on his podcast Stuck with Damon Young season two.

While Young doesn’t consider himself a journalist citing, it’s a vocation bound by facts; he is a prolific writer with bylines in the New York Times, The Washington Post, Ebony, and Time magazine, and a columnist for GQ. According to his bio, Young also co-founded and served as editor-in-chief of VerySmartBrothas, now a vertical at The Root, owned by Univision and Gizmodo Media Group.

His distinctive perspective, musings, and affinity for language bring an engaging insight to discuss the absurdity of human behavior and being Black. Young continues to give his listeners off-the-cuff conversations that correlate to culturally relevant headlines and round-ups of Young’s-approved listener-submitted questions. He boasts interesting dialogue with top-tier special guests like Kiese Laymon, Roy Wood Jrs., Elaine Welteroth, and Nikole Hannah-Jones, to name a few, and each week on Thursdays, his fans can expect a new episode exploring uncomfortable truths of human behavior in all its hideous and hilarious absurd glory.

Yolanda Baruch: What discussion or episode stood out the most to you since launching your podcast? Also, does discussing the absurdity of human behavior and of being Black help to humanize us?

Damon Young: Each episode was heavily scripted, and it was about the collision of self-contradiction and social consciousness. Each guest I had on, we would talk about a particular aspect of that collision, whether it was sex or race or money, religion, parenting, and mental health. The last episode we did was about grief and the performance of grief. I had Bonnie Perry, Hanif Abdurraqib, and Imani Perry on [the show] talking about grief in different ways. How it’s an equilibrium-shifting process that when you add the existing Black thing but the grief thing and how there’s no real curriculum, no girl template for handling grief just as there’s no real curriculum, no real template for existing while being a Black, you have this coalition of assert of absurdities [but] you try to make your way through.

Sometimes you develop great art, sometimes it becomes this albatross you can’t get rid of, and sometimes both. [Regarding] the second part of your question, if a dive into the absurdity and deconstruction of the absurdity humanizes us, maybe, [but] I don’t care. Right. To expound on that, I don’t need to be humanized. I think anyone who believes that Black work is humanizing may already consider us less than human, that’s not a thing that I am interested in, or that’s not what I’m thinking about; humanizing is never a part of our process, or creating something that makes us more human to other people is never a thing that I’m considering while I’m writing [or] podcasting.

Baruch: The title is Stuck with Damon Young. Have you ever had a revelation within your podcast that made you unstuck?

Young: It’s been an ongoing conversation I’ve had internally, with friends, and on the podcast about my relationship with God and religion. There were certain things that I’ve become more confident with admitting out loud [within] the conversation or journey [that] started with the podcast. I had Roy Wood Jr. and Dr. Brittany Cooper on, and we talked about our relationships with God, the church, and Christianity and both segments, I mentioned that I feel like I’m performing.

When I’m in church, where I don’t necessarily feel the Holy Spirit, I don’t feel the presence of God the same way it seems like other Christians seem to, and that’s what I said to Britney, who is also a pastor. I admitted some performance is integral to how we practice Christianity. She also admitted there is some performance, and you’re not singular with that, so thinking about that has continued to evolve into where I am now, where I can evaluate my entire relationship with God, Christianity, and religion. Again, it’s a conversation that started with my podcast.

Baruch: Are you questioning to see if you want to walk away from it, or are you trying to find out where you fit within the whole belief system?

Young: More the latter; I don’t think I’ll be walking away. I’m not agnostic or atheist, but it’s more of an evaluation of my intrigue, how my brain processes everything, and how that has dictated how I process my feelings about God. I’ve dealt with social anxiety; I still deal with anxiety in some capacity, so how much of our relationship with God is anxiety-based if it’s based on fear? That’s not how it’s supposed to be according to when Christians say God is love [but] if God is fear, if my relationship with God is based off of fear [and] terror, perhaps I’m thinking about it wrong or this relationship wrong, and that’s the sort of conversation I wouldn’t have had the confidence to admit out loud, even though I felt that for some time. The podcast episode cleared a path to that confidence where I don’t feel like I’m being blasphemous or getting struck by lightning if I admit to having some ambivalence.

Baruch: You also speak on other topics, as well as the religious angle, like Black masculinity, culturally relevant headlines, fatherhood, male self-image, and the overall Black experience; some of those topics can become a bit heavy, and you serve it with humor. Based on your personal and professional experience, how did you develop your wit, since you describe yourself as an introvert?

Young: I’ve always gravitated to it, and it’s always helped me process and synthesize my understanding of the world around me. I’ve always been the [N-word] with jokes in his head. [and] been the guy who appreciated comedy, humor, I’ve always been drawn to humor as a way to consume stories. Also, as a way to tell stories, that sensibility has permeated and made my work more tactile and visceral because humor is a leveler. It could be a bit of a Trojan horse, where you have this humor that is part of a larger, more serious conversation, and it’s an entry. Then you think that you’re just laughing and joking, then boom, you just learned something and had this intense conversation about masculinity, sexuality, or economic insecurity. Right. I think back to an interview I heard a few years ago with Michaela Coel, where someone asked her why she inserts humor in such a serious subject matter. They were referencing her I May Destroy You, her HBO series, which deals with consent and sexual assault [it’s] a very serious subject matter, but it’s also extremely funny. So her answer was, “I do not insert humor; I just don’t remove it.” I remember when she said that, ‘I was like, Holy sh—, that’s, that’s it? That’s the answer’ because there’s humor all around us; I mean, sh— is absurd[and] wicked funny. Sometimes it takes some perspective to recognize that that was funny, even though it was awful at the moment, and so the funny part is something that I leaned into.

Baruch: You touched upon Black masculinity, which is a topic that you often visit throughout your writing, as well as through the podcast. Do you feel the idea of Black masculinity is constantly evolving?

Young: How we’re socialized to exist is an evolution. We get different images in 2023, like the things I was exposed to; the things that I learned will be different than those that my son is exposed to and the things that he learns then if he decides to have children and happens to have a son, the things that that kid learns and will be exposed to will be different than what my son is learning and being exposed to right now.

So again, it is a constant living and breathing evolution, and the danger, particularly for people my age, I’m 44, we get stuck, and you stop evolving at 16 or 26, and you’re not a part of the world. You are a relic; you’re antagonistic, and that is a fear of mine is to be a person who just stopped to be a living fossil out here saying 1999 sh— in 2023. So evolution is paramount to who I am as a person, husband, dad, friend, co-worker, and writer.

Baruch: Your conversation with Simone Paulin for your episode, You Woke Me Up, was very intriguing. From your perspective, why is wokeism such a threat to so many conservative pundits? Why is Blackness in itself still so threatening?

Young: I mean, it’s the same question. Why is wokeism a threat? Why is Blackness so threatening? When we ask ourselves that question, we have to reevaluate what we mean by threat because when we think of the term threat, we think of a present physical danger. Someone’s going to come to my crib; I feel unsafe outside. I think these conservatives are exaggerating the threat they feel and that all of this is about control. They might feel a threat in the context of ‘We are going to have 1% less control than we did in 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 years ago.’ But all this conversation is just them trying to galvanize their base so that they can have more control of the culture, economy, and political system of business, and that’s what this is about.

I think the fear of wokeness and the fear of Blackness is a red herring where they want to enact control in a very shrewd way. If we get the support behind this boogeyman, we’ll be able to elect more judges and politicians and elect more people who could get our worldview and make it law, and the control doesn’t just stop at wokeness; it’s about controlling women’s bodies, our language, what we can learn. It’s just all about them being in power.

Baruch: You have a section of your podcast where you talk about the things you hate. What are the things that you love?

Young: I love cookies and cream milkshakes even though I’m lactose intolerant. I love playing basketball. I love watching Kyrie Irving play basketball; I do not love listening to him talk all the time. I love topper sneakers. I love my family, wife, kids, dad, and friends. I love that I’ve been privileged enough to make a living by articulating my thoughts. Whether through writing or podcasting, I recognize that I’m deeply privileged. I love hoodies. I love the NBA League pass. I love that I’m in a position where I can afford the NBA League pass. I love driving, so there are a few things.

Baruch: How do you want your listeners to utilize the information you dissect through your conversations?

Young: I want them to be hungry for more so that they continue to listen (laughs), buy my book, and read my articles. I’m keeping it a buck; that’s my goal when people listen to the show to be entertained enough and to like it enough or hated enough to want to come back.

To listen to Damon Young’s podcast visit here.

Read the full article here